"SUNSHINE THROUGH THE RAIN" - Dreams by AKIRA KUROSAWA

“SUNSHINE THROUGH THE RAIN”- Dreams by AKIRA KUROSAWA

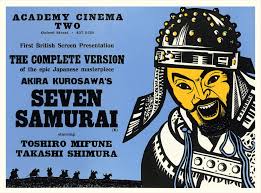

Akira Kurosawa was a Japanese filmmaker. Regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers in the history of cinema, Kurosawa directed 30 films in a career spanning 57 years. Kurosawa was most popular in America and European countries more than his native Japan.

DREAMS - A film based on eight of Kurosawa's dreams. They range from the lyrical to the apocalyptic.

Sunshine

Through The Rain :

There is an old legend in Japan that states that when the sun is shining through the rain, the kitsune (foxes) have their weddings (this is a common theme globally – see sunshower). In this first dream, a boy defies the wish of a woman, possibly his mother, to remain at home during a day with such weather. From behind a large tree in the nearby forest, he witnesses the slow wedding procession of the kitsune. Unfortunately, he is spotted by the foxes and runs. When he tries to return home, the same woman says that a fox had come by the house, leaving behind a tantō knife. The woman gives the knife to the boy, implying that he must commit suicide. The woman asks the boy to go and beg forgiveness from the foxes, although they are known to be unforgiving, refusing to let him in unless he does so. The boy sets off into the mountains, towards the place under the rainbow in search for the kitsune's home.

Please open the above link to view the video of Sunshine Through the Rain – Dreams by Akira

Kurosawa.

The most well-known of

all Japanese directors, the great irony about Akira Kurosawa's career is that

he is far more popular outside of Japan than he is in Japan. The son of an army

officer, Kurosawa studied art before gravitating to film as a means of supporting

himself. He served seven years as an assistant to director Kajiro Yamamoto

before he began his own directorial career with Sanshiro Sugata (1943), a film

about the 19th-century struggle for supremacy between adherents of judo and

ju-jitsu that so impressed the military government, he was prevailed upon to

make a sequel (Sanshiro Sugata Part II).

Following the end of

World War II, Kurosawa's career gathered speed with a series of films that cut

across all genres, from crime thrillers to period dramas -- among the latter,

his Rashomon (1951) became the first postwar Japanese film to find wide favor

with Western audiences, and simultaneously introduced leading man Toshiro

Mifune to Western viewers. It was Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai (1954), however,

that made the largest impact of any of his movies outside of Japan. Although

heavily cut on its original release, this three-hour-plus medieval action

drama, shot with painstaking attention to both dramatic and period detail,

became one of the most popular of Japanese films of all time in the West, and

every subsequent Kurosawa film has been released in the U.S. in some form, even

if many -- most notably The Hidden Fortress (1958) -- were cut down in length.

At the same time, American and European filmmakers began taking a serious look

at Kurosawa's movies as a source of plot material for their own work --

Rashomon was remade as The Outrage, in a western setting, while Yojimbo (The

Bodyguard) was remade by Sergio Leone as A Fistful of Dollars (1964). The Seven

Samurai (1954) fared best of all, serving as the basis for John Sturges' The

Magnificent Seven (which had been the original title of Kurosawa's movie), in

1960; the remake actually did better business in Japan than the original film

did. In the early 1980s, an un-filmed screenplay of Kurosawa's also served as

the basis for Runaway Train (1985), a popular action thriller.

Kurosawa's movies

subsequent to his period thriller Sanjuro (1962) abandoned the action format in

favor of more esoteric and serious drama, including his epic length medical

melodrama Red Beard (1965). In recent years, despite ill-health and the

problems getting financing for his more ambitious films, Kurosawa has remained

the most prominent of Japanese filmmakers. With his Westernized style, Kurosawa

has always found a wider audience and more financing opportunities in Europe

and America than he has in his own country. A sensitive romantic at heart, with

a sentimental streak that occasionally rises forcefully to the surface of his

movies his work probably resembles that of John Ford more closely than it does

any of his fellow Japanese filmmakers.

Born in Tokyo in 1910,

Akira Kurosawa began his career as an assistant director in the years leading

up to World War II. In 1950, he gained international acclaim for the samurai

tale Rashomon, which he followed with such influential films as The

Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood and Yojimbo. After a

difficult period during which he failed to find backing for his projects and

also attempted suicide, his influence on a younger generation of directors led

to the resurrection of his career with the films Kagemusha and Ran.

Kurosawa died in 1998, leaving behind an impressive body of work that has

earned him a place as one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century.

His well-to-do family

can trace its lineage as far back as the 11th century, and the young Kurosawa

was taught

early on that he was a descendant of samurai. But despite this esteemed,

distinctly Japanese background, Kurosawa’s father believed he and his siblings

should be exposed to Western culture as well, so he frequently took them

to see films.

Initially, Kurosawa found himself drawn to art;

after finishing high school, he studied at the Doshisha School of Western

Painting. However, in 1936, his essay application to work at the Photo Chemical

Laboratories film studio caught the eye of Kajirō Yamamoto, one of Japan’s

biggest director’s at that time, who insisted on hiring Kurosawa. Employed as

an assistant director for the next seven years, Kurosawa made about 24 films

with Yamamoto and other directors, and learned, in particular, the importance

of being able to write a good script.

Because he had been labeled unfit for military

service after failing an earlier physical, when Japan entered World War II

Kurosawa was able to stay in Tokyo and continue to work. Despite the inherent

economic hardships of the conflict, it was during this time that Kurosawa was

promoted to director and made his first film, Sanshiro Sugata. A

martial arts picture set in 19th-century Japan, it was released in 1943 and

showcased Kurosawa’s talents as both a writer and director. Kurosawa followed

with the World War II–themed Ichiban utsukushiku in 1944, an

achievement made even sweeter when he married its star, Yōko Yaguchi, the next

year.

For a brief period after the war’s end,

Kurosawa’s budding career was placed on hold by the occupying U.S. forces, but

he returned to filmmaking with his own criticism of Japan’s pre-war militarism,

No Regrets for Our Youth in 1946. Two years later, he

made his first significant breakthrough with Drunken Angel, a

melodrama set in post-war Tokyo that not only demonstrated Kurosawa’s range,

but also marked his first collaboration with actor Toshirō Mifune.

Kurosawa followed his first domestic success with what would become his first international hit, Rashomon (1950), a samurai murder story told from the perspective of four different characters. It is now considered a masterfully innovative storytelling device for the time, but it was met with mixed reactions in Japan. However, its genius was not lost on the international circuit and it won both the Venice Film Festival’s top prize and the Academy Award for best foreign film. Working from a script by Kurosawa, Martin Ritt remade it as the 1964 Western The Outrage. It became the earliest of many of Kurosawa’s works adapted to this genre.

Now recognized as an important voice in cinema, over the course of the next decade, Kurosawa made some of his most influential and entertaining films. In 1952, he released the internationally acclaimed Ikiru and in 1954 the epic Seven Samurai, a homage to Westerns that would later come full circle when it was remade as The Magnificent Seven (1960). Once more demonstrating his range and flair for adaptation, in 1957 Kurosawa released Throne of Blood. A reimagining of Macbeth, it is widely considered to be one of the finest interpretations of Shakespeare’s works. Following on its heels was 1958's Hidden Fortress, the story of princess, her general and their two bumbling peasant companions on a quest to reach home. It marked a milestone as the first film in Japan to make use of the widescreen format, but it is arguably even more important for the influence it had on the young American filmmaker George Lucas, who names Hidden Fortress as a primary influence for Star Wars.

To gain greater artistic freedom in his work, in 1960, Kurosawa started his own production company. His first film from this new venture was Yojimbo (1961), which follows a nameless wandering samurai as he plays the middle between the two warring factions in a small town. Among his most popular and accessible films, Sergio Leone remade it as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), with Clint Eastwood starring as the archetypal “Man with No Name.”

However, despite Kurosawa’s continued successes,

television’s negative impact on filmmaking and an economic depression in Japan

led him to seek work in Hollywood. Unfortunately, none of his projects there

came to fruition. His thriller Runaway Train failed to gain financial

backing and personal differences caused Twentieth Century Fox to fire him from

the Pearl Harbor film Tora! Tora! Tora! Compounding Kurosawa’s

disappointment was the commercial failure of his 1970 comedy, Dodes’ka-den.

Dejected, exhausted and suffering financially, Kurosawa attempted

suicide in 1971. Although he eventually recovered, he resigned himself to

the fact that he would never direct again.

On the verge of fading into obscurity, Kurosawa

was approached by a Russian production company to make the adventure epic Dersu

Uzala about a hermit. Shot on location in Siberia and premiering in

1975, international audiences enthusiastically received the

film. However, the production took a toll on Kurosawa’s health. Although

he was finding it increasingly difficult to win backing for his

projects, Kurosawa persevered in his efforts to bring his vision to the

screen.

For all that Kurosawa had contributed to the world of cinema, it is fitting that his profound influence would someday repaid. In the late ’70s, Kurosawa admirer George Lucas leveraged his massive success with Star Wars to bring Francis Ford Coppola and Twentieth Century Fox on board to produce Kagemusha, a medieval samurai story of epic proportions. Released in 1980, it won the Grand Prize at Cannes and was nominated for best foreign language film at the Academy Awards. Reinvigorated by the success of Kagemusha, Kurosawa followed it up in 1985 with Ran, his samurai adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Dreams

In 1990 the 80-year-old director returned with Dreams, an experimental offering brought to the screen with help from yet another of his admirers, Steven Spielberg. Though the film met with a lukewarm reception, at that year’s Academy Awards Spielberg and Lucas presented Kurosawa with an honorary Oscar by in recognition of his body of work.

The director made the mildly successful Rhapsody

in August in 1990 and Madadayo in 1993. In 1995, he was

working in his next project when he fell and broke his back. The injuries he

sustained confined him to a wheelchair for the remainder of life and led to a

rapid deterioration of his health. He died from a stroke on September 6, 1998,

in Tokyo. He was 88. Since his passing, his impact on film continues to be felt

through new interpretations of his work and the lasting influence he has had on

some of the industry’s brightest lights.

Satyajit Ray Indian Filkmmaker with Akira Kurosawa

Kurosawa Akira,

first Japanese film

director to win international acclaim, with such films as Rashomon

(1950), Ikiru

(1952), Seven

Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood

(1957), Kagemusha (1980), and Ran (1985).

After leaving secondary school, Kurosawa attended an art school and began painting in the Western style. Although he was awarded important art prizes, he gave up his ambition to become a painter and in 1936 became an assistant director in the PCL cinema studio. Until 1943 he worked there mainly as an assistant to Yamamoto Kajirō, one of Japan’s major directors of World War II films. During this period Kurosawa became known as an excellent scenarist. Some of his best scenarios were never filmed but only published in journals; yet they were noticed by specialists for their freshness of representation and were awarded prizes.

In 1943 Kurosawa was promoted to director and

made his first feature film, Sanshiro Sugata,

from his own scenario; this story of Japanese judo masters of the 1880s

scored a great popular success. In 1944 he made his second film, Ichiban

utsukushiku (The Most Beautiful),

a story about girls at work in an arsenal. Immediately thereafter, he married

the actress who had played the leading part in the picture, Yaguchi Yoko; they

had two children, a son and a daughter. In August 1945, when Japan offered to

surrender in World War II,

he was shooting his picture Tora no o fumu otokotachi (They

Who Step on the Tiger’s Tail), a parody of a well-known Kabuki drama. The Allied

occupation forces, however, prohibited the release of most films dealing with

Japan’s feudal past,

and this outstanding comedy was not distributed until 1952.

Kurosawa’s Waga seishun ni kuinashi

(1946; No Regrets for

Our Youth) portrays the history of Japanese militarism from 1933

through the end of the war in terms of a person executed on suspicion of

espionage during the war. Of the many postwar films criticizing Japanese

militarism, this was the most successful, both artistically and commercially.

It was Yoidore tenshi (1948; Drunken Angel),

however, that made Kurosawa’s name famous. This story of a consumptive gangster

and a drunken doctor living in the postwar desolation of downtown Tokyo is a melodrama

intermingling desperation and hope, violence, and melancholy. The gangster was

portrayed by a new actor, Mifune Toshirō,

who became a star through this film and who subsequently appeared in most of

Kurosawa’s films.

Kurosawa’s Rashomon

was shown at the Venice

Film Festival in 1951 and was awarded the Grand Prix. It also won the Academy Award for best

foreign-language film. This was the first time a Japanese film had won such

high international acclaim, and Japanese films now attracted serious attention

all over the world. An adaptation of two short stories written by Akutagawa

Ryūnosuke, the film deals with a samurai, his wife, a bandit,

and a woodcutter in the 10th century; a rape and a murder are recollected by

the four persons in distinctly different ways. This presentation of the same

event as seen by different persons caught the imagination of the audience and

advanced the idea of cinema as a means of probing a metaphysical problem.

Ikiru (“To Live”) is

regarded by many critics as one of the finest works in the history of the

cinema. It concerns a petty governmental official who learns he has only half a

year until he will die from cancer. He searches for solace in the affection of

his family but is betrayed, then seeks enjoyment but becomes disillusioned,

and, in the end, is redeemed by using his position to work for the poor. In

this film, which abounds in strong moral messages, Kurosawa depicts in an

extremely realistic manner the collapse of the family system, as well as the

hypocritical aspects of officials in postwar Japanese society. The picture was

an outstanding document of the life and the spiritual situation of Japanese

people, who were then beginning to recover from the desperation caused by

defeat in the war.

The epic Shichinin no samurai (Seven

Samurai) is considered the most entertaining of Kurosawa’s films and

also his greatest commercial success. It depicts a village of peasants and a

few leaderless samurai who fight for the village against a gang of marauding

bandits; although it was inspired by his admiration of Hollywood Westerns, it

was executed in an entirely Japanese style.

Ikimono no kiroku (1955; I Live in

Fear, or Record of a

Living Being) is a deeply honest film portraying a Japanese foundry

owner’s terror of the atomic tests conducted by the United States and the

Soviet Union. Its pessimistic conclusion, however, made it a commercial

failure.

Kurosawa was also noted for his adaptations of

European literary classics into films with Japanese settings. Hakuchi

(1951; The

Idiot) is based upon Fyodor

Dostoyevsky’s novel of the same title, Kumonosu-jo (Throne

of Blood) was adapted from Shakespeare’s

Macbeth,

and Donzoko (1957; The

Lower Depths) was from Maksim Gorky’s

drama: each of these films is skillfully Japanized. Throne of Blood,

which reflects the style of the sets and acting of the Japanese Noh play and uses not a

word of the original text, has been called the best film of all the countless

cinematized Shakespearean dramas.

Kurosawa’s pictures contributed a strong sense of

style to the artistic Japanese film, which had been pursuing a naturalistic

trend. The violent action of his more commercial works also exerted a powerful

influence.

In 1960 he set up Kurosawa Productions, of which

he became president, and began to produce his own works. As producer, however,

he was continually embarrassed by economic difficulties. Throughout the 1960s,

Kurosawa made a number of entertainment films,

mainly with samurai as leading characters; Yojimbo (1961; “The

Bodyguard”) is a representative work. Akahige (1965; Red Beard) combines

elements of entertainment with a sentimental humanism. In the 1960s, however,

Japanese cinema fell into an economic depression, and Kurosawa’s plans, in most

cases, were found by film companies to be too expensive. As a result, Kurosawa

attempted to work with Hollywood producers, but each of the projects ended in

failure. At the Kyōto

studio in 1968, for 20th

Century Fox, he started shooting Tora, Tora, Tora!,

a war film dealing with the air attack on Pearl

Harbor. The work progressed slowly, however, and the producer, fearing an

excess in estimated cost, dismissed Kurosawa and replaced him with another director.

After a six-year interval, Kurosawa at last managed to present another of his

films, Dodesukaden (1970; Dodeskaden). His

first work in colour, a comedy of poor people living in slums, it recaptured

much of the poignancy of his best works but failed financially. The period of

personal despondency and artistic silence that followed ended in the mid-1970s

when Kurosawa filmed Dersu

Uzala (1975) in Siberia

at the invitation of the Soviet government. This story of a Siberian hermit won

wide acclaim.

Kagemusha (“The

Shadow Warrior”), released in 1980, was the director’s first samurai film in 14

years. It concerns a petty thief who is chosen to impersonate a powerful feudal

lord killed in battle. This film was notable for its powerful battle scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, Ran (1985; “Chaos”), was an

even more successful samurai epic. An adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear set in

16th-century Japan, the film uses sons instead of daughters as the aging

monarch’s ungrateful children. Ran was acclaimed as one of Kurosawa’s

greatest films in the grandeur of its imagery, the intellectual depth of its

screen adaptation, and the intensity of its dramatic performances. His last

three films—Dreams (1990), Rhapsody in August (1990), and Madadayo

(1993)—were not as well received.

Although other Japanese filmmakers acquired substantial international followings after the pioneering success of Rashomon, Kurosawa’s films continue to command great interest in the West. They represent a unique combination of elements of Japanese art—in the subtlety of their feeling and philosophy, the brilliance of their visual composition, and their treatment of samurai and other historic Japanese themes—with a distinctly Western feeling for action and drama and a frequent use of stories from Western sources, both literary classics and popular thrillers. Kurosawa was a recipient of numerous film and career honours, including a Golden Lion for Career Achievement at the 1982 Venice Film Festival, an Academy Award for lifetime achievement (1989), the Directors Guild of America’s lifetime achievement award (1992), and the Japan Art Association’s Praemium Imperiale prize for theatre/film (1992).

Filmography

Writer | Director | Second Unit Director or Assistant Director | Editor | Producer | Soundtrack | Sound department | Miscellaneous Crew | Thanks | Self | Archive footage

2013

Stray

Dog (TV Movie) (based on a script by)

2011

The

Outrage (based on screenplay by)

2008

Hidden

Fortress: The Last Princess (original screenplay)

2007

Tsubaki

Sanjûrô (screenplay)

2004

Samurai

7 (TV Series) (film "Shichinin no samurai" - 26 episodes)

- The Last Battle

(2004) ... (film "Shichinin no samurai")

- The Era's End

(2004) ... (film "Shichinin no samurai")

- The Oaths

(2004) ... (film "Shichinin no samurai")

- The Lies

(2004) ... (film "Shichinin no samurai")

- The Rescue

(2004) ... (film "Shichinin no samurai")

2002

The

Sea Is Watching (original screenplay)

2000

Dora-heita

(screenplay)

1999

After

the Rain (screenplay)

1996

Last

Man Standing (story)

1993

Maadadayo

(writer)

1991

Rhapsody

in August

1990

Akira

Kurosawa's Dreams (written by)

1985

Runaway

Train (based on a screenplay by)

1985

Ran

(screenplay)

1980

Kagemusha

1975

Dersu

Uzala (screenplay - as Akira Kurosava)

1973

Nora

inu (1949 screenplay)

1970

Dodes'ka-den

(screenplay)

1970

Tora!

Tora! Tora! (Japanese sequences - uncredited)

1968

The

Last Day of Hsianyang (screenplay)

1965

Sanshiro

Sugata (1943 screenplay "Sugata Sanshiro" and 1945 screenplay

"Zoku Sugata Sanshiro")

1965

Red

Beard (screenplay)

1964

The

Outrage (screenplay "Rashomon")

1964

Jakoman

to Tetsu (and earlier screenplay)

1963

High

and Low (screenplay)

1962

Fencing

Master (1950 screenplay Tateshi danpei)

1962

Sanjuro

(screenplay)

1961

Yojimbo

(screenplay) / (story)

1960

Play

of the Week (TV Series) (teleplay - 1 episode)

- Rashomon

(1960) ... (teleplay)

1960

The

Magnificent Seven (screenplay "Shichinin no samurai" -

uncredited)

1960

The

Bad Sleep Well (written by)

1959

The

Saga of the Vagabonds (writer)

1958

The

Hidden Fortress (written by)

1957

Nichiro

sensô shôri no hishi: Tekichû ôdan sanbyaku-ri (earlier screenplay

"Techiku odan sanbyaku ri") / (screenplay)

1957

Donzoko

1957

Throne

of Blood (screenplay)

1955

Sanshiro

Sugata

1955

I

Live in Fear (story)

1955

Asunaro

monogatari (screenplay)

1955

Kieta

chutai

1954

Seven

Samurai (screenplay)

1953

My

Wonderful Yellow Car (writer)

1952

Ikiru

(written by)

1952

Sword

for Hire

1951

Kedamono

no yado

1951

The

Idiot

1951

Beyond

Love and Hate

1950

Rashomon

(screenplay)

1950

Tateshi

Danpei

1950

Jiruba

Tetsu

1950

Scandal

1950

Desertion

at Dawn

1949

Stray

Dog (writer)

1949

Jakoman

and Tetsu (writer)

1949

Jigoku

no kifujin (writer)

1949

The

Quiet Duel (writer)

1948

The

Portrait (writer)

1948

Drunken

Angel (written by)

1947

Snow

Trail

1947

One

Wonderful Sunday

1947

Four

Love Stories (segment "Hatsukoi")

1946

No

Regrets for Our Youth (uncredited)

1945

Zoku

Sugata Sanshirô

1945

Appare

Isshin Tasuke

1944

Ichiban

utsukushiku

1944

Dohyosai

1943

Sanshiro

Sugata (writer)

1942

Tsubasa

no gaika

1942

Currents

of Youth

Akira Kurosawa is dreaming big in the heavens for us to get entertained and enriched when we finally make it there.

KUROSAWA IS A TRUE GENIUS WHEN HE IS

DREAMING……!!!!

I consider it as a privilege to

having featured Akira Kurosawa in JOHNNY’S BLOG.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home