"If you want to be happy, Be Happy" - LEO TOLSTOY

“If you want to be happy, Be Happy” - LEO

TOLSTOY

The most famous quote of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy being “If you want to be happy, be”.

If you want to be

happy, Bee... Honey…!!

The Honey Bee collects

the precious Honey which makes it rich.

One of the inevitable factors which bring you happiness is money and

richness. If you want to learn about the

hard work put in by honey bee to collect honey to make its honey comb rich is a

precious habit to imbibe, if not inherited.

If you amass richness by your endeavors, your partner, sweet heart “Honey”

will be happy with more than enough to fill the shopper’s basket and for sure

you will ensure that your glass is always half-full.

Leo Tolstoy is a legendary Russian writer who enriched the world literature in his own way and with inimitable style of writing which skill is difficult to emulate.

Leo Tolstoy was an inspiration for Nobel Laureate Russian writers Mikhail Sholokhov (And Quite Flows the Don fame – Nobel Prize 1965) and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Nobel Prize 1970). Fyodor Dostoyevski is another famous Russian writer (Crime and Punishment fame) who has been greatly influenced by Leo Tolstoy.

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy ( 28

August,1828 – 20 November,1910), usually referred to in English as Leo

Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest

authors of all time.

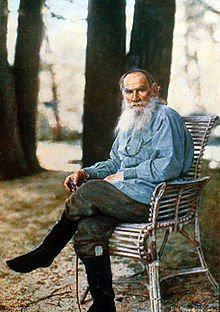

Leo Tolstoy

The first color photo taken in Russia – 1908

Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828,

he is best known for the novels War

and Peace (1869) and Anna

Karenina (1877), often cited as pinnacles of realist

fiction. He first achieved literary acclaim in his twenties with his

semi-autobiographical trilogy, Childhood, Boyhood,

and Youth (1852–1856), and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), based upon

his experiences in the Crimean War. Tolstoy's fiction includes dozens of short

stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Family

Happiness, and Hadji Murad. He also wrote plays

and numerous philosophical essays.

On September 9, 1828, writer Leo Tolstoy was born

at his family's estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in the Tula Province of Russia. He was

the youngest of four boys. In 1830, when Tolstoy's mother, née Princess

Volkonskaya, died, his father's cousin took over caring for the children. When

their father, Count Nikolay Tolstoy, died just seven years later, their aunt

was appointed their legal guardian. When the aunt passed away, Tolstoy and his

siblings moved in with a second aunt, in Kazan, Russia. Although Tolstoy

experienced a lot of loss at an early age, he would later idealize his

childhood memories in his writing.

Tolstoy received his primary education at home,

at the hands of French and German tutors. In 1843, he enrolled in an Oriental

languages program at the University of Kazan. There, Tolstoy failed to excel as

a student. His low grades forced him to transfer to an easier law program.

Prone to partying in excess, Tolstoy ultimately left the University of Kazan in

1847, without a degree. He returned to his parents' estate, where he made a go

at becoming a farmer. He attempted to lead the serfs, or farmhands, in their

work, but he was too often absent on social visits to Tula and Moscow. His stab

at becoming the perfect farmer soon proved to be a failure. He did, however,

succeed in pouring his energies into keeping a journal—the beginning of a

lifelong habit that would inspire much of his fiction.

Leo Tolstoy dressed in Peasant Clothing

As Tolstoy was flailing on the farm, his older

brother, Nikolay, came to visit while on military leave. Nikolay convinced

Tolstoy to join the Army as a junker, south in the Caucasus Mountains, where

Nikolay himself was stationed. Following his stint as a junker, Tolstoy

transferred to Sevastopol in Ukraine in November 1854, where he fought in the

Crimean War through August 1855.

During quiet periods while Tolstoy was a junker

in the Army, he worked on an autobiographical story called Childhood.

In it, he wrote of his fondest childhood memories. In 1852, Tolstoy submitted

the sketch to The Contemporary, the most popular journal of the time.

The story was eagerly accepted and became Tolstoy's very first published work.

After completing Childhood, Tolstoy

started writing about his day-to-day life at the Army outpost in the Caucasus.

However, he did not complete the work, entitled The Cossacks, until

1862, after he had already left the Army.

Amazingly, Tolstoy still managed to continue

writing while at battle during the Crimean War. During that time, he composed Boyhood

(1854), a sequel to Childhood, the second book in what was to become

Tolstoy's autobiographical trilogy. In the midst of the Crimean War, Tolstoy

also expressed his views on the striking contradictions of war through a

three-part series, Sevastopol Tales. In the second Sevastopol

Tales book, Tolstoy experimented with a relatively new writing technique:

Part of the story is presented in the form of a soldier's stream of

consciousness.

Once the Crimean War ended and Tolstoy left the

Army, he returned to Russia. Back home, the burgeoning author found himself in

high demand on the St. Petersburg literary scene. Stubborn and arrogant,

Tolstoy refused to ally himself with any particular intellectual school of

thought. Declaring himself an anarchist, he made off to Paris in 1857. Once

there, he gambled away all of his money and was forced to return home to

Russia. He also managed to publish Youth, the third part of his

autobiographical trilogy, in 1857.

Back in Russia in 1862, Tolstoy produced the

first of a 12 issue-installment of the journal Yasnaya Polyana,

marrying a doctor's daughter named Sofya Andreyevna Bers that same year.

Residing at Yasnaya Polyana with his wife and

children, Tolstoy spent the better part of the 1860s toiling over his first

great novel, War and Peace. A portion of the novel was first published

in the Russian Messenger in 1865, under the title "The Year

1805." By 1868, he had released three more chapters. A year later, the

novel was complete. Both critics and the public were buzzing about the novel's

historical accounts of the Napoleonic Wars, combined with its thoughtful

development of realistic yet fictional characters. The novel also uniquely

incorporated three long essays satirizing the laws of history. Among the ideas

that Tolstoy extols in War and Peace is the belief that the quality

and meaning of one's life is mainly derived from his day-to-day activities.

Following the success of War and Peace,

in 1873, Tolstoy set to work on the second of his best known novels, Anna

Karenina. Anna Karenina was partially based on current events

while Russia was at war with Turkey. Like War and Peace, it

fictionalized some biographical events from Tolstoy's life, as was particularly

evident in the romance of the characters Kitty and Levin, whose relationship is

said to resemble Tolstoy's courtship with his own wife.

The first sentence of Anna Karenina is

among the most famous lines of the book: "All happy families resemble one

another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Anna Karenina

was published in installments from 1873 to 1877, to critical and public

acclaim. The royalties that Tolstoy earned from the novel contributed to his

rapidly growing wealth.

Despite the success of Anna Karenina,

following the novel's completion, Tolstoy suffered a spiritual crisis and grew

depressed. Struggling to uncover the meaning of life, Tolstoy first went to the

Russian Orthodox Church, but did not find the answers he sought there. He came

to believe that Christian churches were corrupt and, in lieu of organized

religion, developed his own beliefs. He decided to express those beliefs by

founding a new publication called The Mediator in 1883.

As a consequence of espousing his

unconventional—and therefore controversial—spiritual beliefs, Tolstoy was

ousted by the Russian Orthodox Church. He was even watched by the secret

police. When Tolstoy's new beliefs prompted his desire to give away his money,

his wife strongly objected. The disagreement put a strain on the couple's

marriage, until Tolstoy begrudgingly agreed to a compromise: He conceded to

granting his wife the copyrights—and presumably the royalties—to all of his

writing predating 1881.

In addition to his religious tracts, Tolstoy

continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Among his later

works' genres were moral tales and realistic fiction. One of his most

successful later works was the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich,

written in 1886. In Ivan Ilyich, the main character struggles to come

to grips with his impending death. The title character, Ivan Ilyich, comes to

the jarring realization that he has wasted his life on trivial matters, but the

realization comes too late.

In 1898, Tolstoy wrote Father Sergius, a

work of fiction in which he seems to criticize the beliefs that he developed

following his spiritual conversion. The following year, he wrote his third

lengthy novel, Resurrection. While the work received some praise, it

hardly matched the success and acclaim of his previous novels. Tolstoy's other

late works include essays on art, a satirical play called The Living Corpse

that he wrote in 1890, and a novella called Hadji-Murad (written in

1904), which was discovered and published after his death.

Over the last 30 years of his life, Tolstoy

established himself as a moral and religious leader. His ideas about nonviolent

resistance to evil influenced the likes of social leader Mahatma Gandhi.

Also during his later years, Tolstoy reaped the

rewards of international acclaim. Yet he still struggled to reconcile his

spiritual beliefs with the tensions they created in his home life. His wife not

only disagreed with his teachings, she disapproved of his disciples, who

regularly visited Tolstoy at the family estate. Their troubled marriage took on

an air of notoriety in the press. Anxious to escape his wife's growing

resentment, in October 1910, Tolstoy, his daughter, Aleksandra, and his

physician, Dr. Dushan P. Makovitski, embarked on a pilgrimage. Valuing

their privacy, they traveled incognito, hoping to dodge the press, to no avail

Unfortunately, the pilgrimage proved too arduous

for the aging novelist. In November 1910, the stationmaster of a train depot in

Astapovo, Russia opened his home to Tolstoy, allowing the ailing writer to

rest. Tolstoy died there shortly after, on November 20, 1910. He was buried at

the family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in Tula Province, where Tolstoy had lost so

many loved ones yet had managed to build such fond and lasting memories of his

childhood. Tolstoy was survived by his wife and their brood of 8 children. (The

couple had spawned 13 children in all, but only 10 had survived past infancy.)

To this day, Tolstoy's novels are considered

among the finest achievements of literary work. War and Peace is, in

fact, frequently cited as the greatest novel ever written. In contemporary

academia, Tolstoy is still widely acknowledged as having possessed a gift for

describing characters' unconscious motives. He is also championed for his

finesse in underscoring the role of people's everyday actions in defining their

character and purpose.

Novels

- Childhood (1852) – Volume 1 of 'Autobiographical Trilogy'

- Boyhood ,(1854) – Volume 2 of 'Autobiographical Trilogy'

- Youth, (1856) – Volume 3 of 'Autobiographical Trilogy'

- The Cossacks , (1863)

- War and Peace , (1869)

- Anna Karenina ,(1877)

- Resurrection , (1899)

Novellas

- Family Happiness,(1859)

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich , (1886)

- The Kreutzer Sonata,(1889)

- The Forged Coupon ,( 1911)

- Hadji Murat ,( 1912)

Short stories

|

|

Plays

- The Power of Darkness , (1886)

- The First Distiller (1886)

- The Light Shines in Darkness (1890)

- The Fruits of Enlightenment ,( 1891)

- The Living Corpse , (1900)

- The Cause of it All (1910)

Non-fiction

Philosophical works

- A Confession (1879) – Volume 1 of an untitled four-part work[1]

- A Criticism of Dogmatic Theology (1880) – Volume 2 of an untitled four-part work

- The Gospel in Brief, or A Short Exposition of the Gospel (1881)

- The Four Gospel Unified and Translated (1881) – Volume 3 of an untitled four-part work

- Church and State (1882)

- What I Believe (also called My Religion) (1884) – Volume 4 of an untitled four-part work

- What Is to Be Done? (also translated as What Then Must We Do?) (1886)

- On Life (1887)

- The Love of God and of One's Neighbour (1889)

- Supplementary essay for Timofei Bondarev's The Triumph of the Farmer or Industry and Parasitism (1888)

- Why Do Men Intoxicate Themselves? (1890)

- The First Step: on vegetarianism (1892)

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1893)

- Non-Activity (1893)

- The Meaning of Refusal of Military Service (1893)

- Reason and Religion (1894)

- Religion and Morality (1894)

- Christianity and Patriotism (1894)

- Non-Resistance: letter to Ernest H. Crospy (1896)

- How to Read the Gospels (1896)

- The Deception of the Church (1896)

- Letter to the Liberals[2] (1898)

- Christian Teaching (1898)

- On Suicide (1900)

- The Slavery of Our Times (1900)

- Thou Shalt Not Kill (1900)

- Reply to the Holy Synod (1901)

- The Only Way (1901)

- On Religious Toleration (1901)

- What Is Religion and What is its Essence? (1902)

- To the Orthodox Clergy (1903)

- Thoughts of Wise Men (compilation; 1904)

- The Only Need (1905)

- The Grate Sin (1905)

- A Cycle of Reading (compilation; 1906)

- Do Not Kill (1906)

- Love Each Other (1906)

- An Appeal to Youth (1907)

- The Law of Love and the Law of Violence (1908)[3]

- The Only Command (1909)

- A Calendar of Wisdom ; compilation; (1909)

Works on art and literature

- What Is Art? (1897)

- Art and Not Art (1897)

- Shakespeare and the Drama (1909)

Pedagogical works

- Articles from Tolstoy's journal on education, "Yasnaya Polyana" (1861–1862)

- A Primer (1872)

- On Popular Instruction (1874)

- A New Primer (1875)

ANNA KARENINA

– 2012 BRITISH MOVIE

Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina was made into a

blockbuster motion picture in 2012 starring Keira Knightley and Jude Law. It is a great romantic drama film directed

by Joe Wright.

The Oblonsky family of Moscow is torn apart by adultery. Dolly Oblonskaya has caught her husband, Stiva, having an affair with their children’s former governess, and threatens to leave him. Stiva is somewhat remorseful but mostly dazed and uncomprehending. Stiva’s sister, Anna Karenina, wife of the St. Petersburg government official Karenin, arrives at the Oblonskys’ to mediate. Eventually, Anna is able to bring Stiva and Dolly to a reconciliation.

Meanwhile, Dolly’s younger sister, Kitty, is courted by two suitors: Konstantin Levin, an awkward landowner, and Alexei Vronsky, a dashing military man. Kitty turns down Levin in favor of Vronsky, but not long after, Vronsky meets Anna Karenina and falls in love with her instead of Kitty. The devastated Kitty falls ill. Levin, depressed after having been rejected by Kitty, withdraws to his estate in the country. Anna returns to St. Petersburg, reflecting on her infatuation with Vronsky, but when she arrives home she dismisses it as a fleeting crush.

The Oblonsky family of Moscow is torn apart by adultery. Dolly Oblonskaya has caught her husband, Stiva, having an affair with their children’s former governess, and threatens to leave him. Stiva is somewhat remorseful but mostly dazed and uncomprehending. Stiva’s sister, Anna Karenina, wife of the St. Petersburg government official Karenin, arrives at the Oblonskys’ to mediate. Eventually, Anna is able to bring Stiva and Dolly to a reconciliation.

Meanwhile, Dolly’s younger sister, Kitty, is courted by two suitors: Konstantin Levin, an awkward landowner, and Alexei Vronsky, a dashing military man. Kitty turns down Levin in favor of Vronsky, but not long after, Vronsky meets Anna Karenina and falls in love with her instead of Kitty. The devastated Kitty falls ill. Levin, depressed after having been rejected by Kitty, withdraws to his estate in the country. Anna returns to St. Petersburg, reflecting on her infatuation with Vronsky, but when she arrives home she dismisses it as a fleeting crush.

Vronsky, however, follows Anna to St. Petersburg,

and their mutual attraction intensifies as Anna begins to mix with the

freethinking social set of Vronsky’s cousin Betsy Tverskaya. At a party, Anna

implores Vronsky to ask Kitty’s forgiveness; in response, he tells Anna that he

loves her. Karenin goes home from the party alone, sensing that something is

amiss. He speaks to Anna later that night about his suspicions regarding her

and Vronsky, but she curtly dismisses his concerns.

Sometime later, Vronsky participates in a

military officers’ horse race. Though an accomplished horseman, he makes an

error during the race, inadvertently breaking his horse’s back. Karenin notices

his wife’s intense interest in Vronsky during the race. He confronts Anna

afterward, and she candidly admits to Karenin that she is having an affair and

that she loves Vronsky. Karenin is stunned.

Kitty, meanwhile, attempts to recover her health

at a spa in Germany, where she meets a pious Russian woman and her do-gooder

protégée, Varenka. Kitty also meets Levin’s sickly brother Nikolai, who is also

recovering at the spa.

Levin’s intellectual half-brother, Sergei

Koznyshev, visits Levin in the country and criticizes him for quitting his post

on the local administrative council. Levin explains that he resigned because he

found the work bureaucratic and useless. Levin works enthusiastically with the

peasants on his estate but is frustrated by their resistance to agricultural

innovations. He visits Dolly, who tempts him with talk of reviving a

relationship with Kitty. Later, Levin meets Kitty at a dinner party at the

Oblonsky household, and the two feel their mutual love. They become engaged and

marry.

Karenin rejects Anna’s request for a divorce. He

insists that they maintain outward appearances by staying together. Anna moves

to the family’s country home, however, away from her husband. She encounters

Vronsky often, but their relationship becomes clouded after Anna reveals she is

pregnant. Vronsky considers resigning his military post, but his old ambitions

prevent him.

Karenin, catching Vronsky at the Karenin country

home one day, finally agrees to divorce. Anna, in her childbirth agony, begs

for Karenin’s forgiveness, and he suddenly grants it. He leaves the divorce

decision in her hands, but she resents his generosity and does not ask for a

divorce. Instead, Anna and Vronsky go to Italy, where they lead an aimless

existence. Eventually, the two return to Russia, where Anna is spurned by

society, which considers her adultery disgraceful. Anna and Vronsky withdraw

into seclusion, though Anna dares a birthday visit to her young son at

Karenin’s home. She begins to feel great jealousy for Vronsky, resenting the

fact that he is free to participate in society while she is housebound and

scorned.

Married life brings surprises for Levin,

including his sudden lack of freedom. When Levin is called away to visit his

dying brother Nikolai, Kitty sparks a quarrel by insisting on accompanying him.

Levin finally allows her to join him. Ironically, Kitty is more helpful to the

dying Nikolai than Levin is, greatly comforting him in his final days.

Kitty discovers she is pregnant. Dolly and her

family join Levin and Kitty at Levin’s country estate for the summer. At one

point, Stiva visits, bringing along a friend, Veslovsky, who irks Levin by

flirting with Kitty. Levin finally asks Veslovsky to leave. Dolly decides to

visit Anna, and finds her radiant and seemingly very happy. Dolly is impressed

by Anna’s luxurious country home but disturbed by Anna’s dependence on

sedatives to sleep. Anna still awaits a divorce.

Levin and Kitty move to Moscow to await the birth

of their baby, and they are astonished at the expenses of city life. Levin

makes a trip to the provinces to take part in important local elections, in

which the vote brings a victory for the young liberals. One day, Stiva takes

Levin to visit Anna, whom Levin has never met. Anna enchants Levin, but her

success in pleasing Levin only fuels her resentment toward Vronsky. She grows

paranoid that Vronsky no longer loves her. Meanwhile, Kitty enters labor and

bears a son. Levin is confused by the conflicting emotions he feels toward the

infant. Stiva goes to St. Petersburg to seek a cushy job and to beg Karenin to

grant Anna the divorce he once promised her. Karenin, following the advice of a

questionable French psychic, refuses.

Anna picks a quarrel with Vronsky, accusing him

of putting his mother before her and unfairly postponing plans to go to the

country. Vronsky tries to be accommodating, but Anna remains angry. When

Vronsky leaves on an errand, Anna is tormented. She sends him a telegram

urgently calling him home, followed by a profusely apologetic note. In

desperation, Anna drives to Dolly’s to say goodbye, and then returns home. She

resolves to meet Vronsky at the train station after his errand, and she rides

to the station in a stupor. At the station, despairing and dazed by the crowds,

Anna throws herself under a train and dies.

Two months later, Sergei’s book has finally been

published, to virtually no acclaim. Sergei represses his disappointment by

joining a patriotic upsurge of Russian support for Slavic peoples attempting to

free themselves from Turkish rule. Sergei, Vronsky, and others board a train

for Serbia to assist in the cause. Levin is skeptical of the Slavic cause,

however.

Kitty becomes worried by Levin’s gloomy mood. He has

become immersed in questions about the meaning of life but feels unable to

answer them. One day, however, a peasant remarks to Levin that the point of

life is not to fill one’s belly but to serve God and goodness. Levin receives

this advice as gospel, and his life is suddenly transformed by faith.

Later that day, Levin, Dolly, and Dolly’s

children seek shelter from a sudden, violent thunderstorm, only to discover

that Kitty and Levin’s young son are still outside. Levin runs to the woods and

sees a huge oak felled by lightning. He fears the worst, but his wife and child

are safe. For the first time, Levin feels real love for his son, and Kitty is

pleased. Levin reflects again that the meaning of his life lies in the good

that he can put into it.

In Tolstoy, the theatre is often something to be mistrusted, both as art-form and social occasion, a place of absurdity and vanity either side of the footlights. Famously, the one thing he personally disliked in Chekhov was his habit of writing for the theatre, and said to him: "Shakespeare's plays are bad enough, but yours are even worse!" So it is an interesting, even subversive idea for screenwriter Tom Stoppard and director Joe Wright to have contrived an adaptation of Anna Karenina set in one place: a theatre.

Here is where the show and theatricality of high

society is underlined, where the norms and hypocrisies of public life are

conspicuous. Scenes will begin in the theatre building, on stage, or in an

auditorium where the seats have been removed, often among costumed extras who

will freeze like waxworks while the principals exchange dialogue. Or sometimes,

characters will tensely quarrel backstage amid the ropes and pulleys

controlling the scenery. This approach gives the scenes which really are set at

the theatre a hyperreal quality, though the film's action will at times open

out into the normal sets and outdoor locations of a regular adaptation.

It's a magic lantern effect, a rhetoric of

unreality. The group scenes often make the film look like a musical without the

songs. It sometimes has the effect of re-focusing our attention all the more

sharply on to the performances, although I sometimes felt that it should either

be done completely stylised or not at all, an absolute one-location movie, or a

conventional one ranging far afield.

Keira Knightley is very good as Anna, suggesting

a new subtlety and maturity in her acting. She is the artless wife and mother,

married to a pinched and prim government official, Alexei Karenin. In this

role, too, Jude Law gives a thoroughly intelligent performance. Bearded and

bespectacled, he behaves like an ascetic or a priest who increasingly

disapproves both of others' weakness and his own enforced tolerance. Anna has

come to Moscow from her St Petersburg home on a mission of mercy: her scapegrace

brother Oblonsky (Matthew Macfadyen) has been caught by his wife Dolly (Kelly

Macdonald) having an affair with the family's former governess. (Oblonsky's is

the unhappy family described in the book's famous opening sentence; where all

happy families are alike, his is "unhappy in its own way".) Anna,

with her delicacy and tact must speak to Dolly, persuade her to forgive and

forget and keep the marriage together. Yet through an ironic wrench of fate, it

is on this visit that she meets the mercurial and handsome young army officer,

Count Vronsky, played by Aaron

Taylor-Johnson. There is a spark between them, and Anna finds herself set

on a terrible, fateful path.

The film version skates over that other half of

the story which concerns Oblonsky's friend Levin, played by Domhnall Gleeson, a

wealthy idealist who has come to town to propose to the beautiful Kitty (Alicia

Vikander), also being courted by Vronsky, but deeply wounded and downcast is

forced to retreat to his country estates and find some consolation in pursuing

a life of simplicity, close to the land and to God. His story is hardly as

sensational and dramatic as Anna's, and yet without the mystery of seeing

Levin's life juxtaposed with hers — they actually have a connection in the

book, not hinted at here — the story loses some of its perspective and its

flavour. Gleeson does well in this demanding role, reduced though it is.

As Vronsky, Aaron Taylor-Johnson certainly brings

conceit and a callow self-regard. He preens well. As in his earlier movies Kick-Ass and Nowhere Boy,

he is an attractive, open presence, but he is out of his depth here, especially

when he has to suggest Vronsky's later agony and wretchedness, and the fact

that he, as well as Anna, has made sacrifices for their affair.

And so the tale continues, interestingly, if

somewhat disconcertingly, in this semi-permeable fantasy theatre, from which

the characters make their periodic excursions into the outside world. It is

probably most startling when the racecourse scene is actually held indoors, in

the theatre. The horses parade round and round the auditorium itself. That's

certainly striking, though audiences of a more down-to-earth cast of mind could

be forgiven for wondering what the smell would be like, and where the guys with

shovels are standing.

More successful, and more moving, is a tableau

later in the film which shows the gentle meadow where Karenin comes to terms

with his memories, or perhaps it is rather the meadow where Anna had her most

ecstatic intimacy with Vronsky. Surreally, miraculously, this meadow is spread

over the theatre; the building is carpeted with flowers. A dream of freedom and

contentment has spread itself out in a place which until then had been a venue

for anxiety and unhappiness. The Wright/Stoppard Anna Karenina is not a total

success, but it's a bold and creative response to the novel.

Anna Karinena is truly a director’s movie and

Joe Wright deserves kudos for this venture.Anna Karenina’s role was essayed by Greta Garbo, Vivien Leigh and Sophie Marceau on silver screen prior to Keira Knightley.

Leo Tolstoy’s works “Anna Karenina” and “War and

Peace” was widely admired by literature lovers across the world. Leo Tolstoy’s work “The Kingdom of God is

within you” has fascinated Mahatma Gandhi.

“A Letter to a Hindu” was one of Tolstoy’s another work.

Leo Tolstoy’s “WAR AND PEACE” Epic in scale is

regarded as one of the central works of world literature.

Leo Tolstoy is undoubtedly one of the all time

great author in the world literature and surely merits a mention in JOHNNY’S BLOG.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home